“The wise man sees a different tree from the fool.”

William Blake

When you look at a tree, what do you see? Imagine that we ask this question to a class of teenagers as they near the end of their schooling. What would they say? Would Blake say that they had answered “wisely” or “foolishly”?

This piece will examine the merits of asking such questions in our schools, and what the responses might suggest about the education schools are providing. My hunch is that our class of teenagers would answer something like the following. Some would no doubt believe the question itself to be foolish but most would be eager to prove how well they had absorbed the GCSE Science curriculum. “We see… photosynthesis in action! … the lungs of our planet! …the heart of our ecosystem! …home to bugs and birds! …logs for the winter fire! …a table for dinner! … employment for timber merchants and lumberjacks.” And so on. My hunch is that few children would answer in the manner of a John Muir (“between every two pines is a doorway to a new world”) or a Coleridge or a Roger Deakin (“to enter a wood is to pass into a different world in which we ourselves are transformed”). And that this is less because they lack the means of expression than that they lack of the means of feeling.

In other words, like many who argue in favour of trees, if a teenager cares about trees today, though she may be appalled by the threats of deforestation and climate change, she will likely do so for reasons that rarely rise above the utilitarian. If this is true, it should trouble us as teachers because it means that a richer relationship with the natural world has not been disclosed to her. Children are being left blind to a relationship with trees that previous generations took for granted and which they themselves might have felt in an earlier stage of development. They are seeing in a sense half a tree; an impoverished and lifeless thing robbed of any larger meaning. And though I have chosen to write about trees, substitute almost any proper noun you care to think of: homes, horses and historical figures have been similarly cut down to size.

We might call this “richer relationship” a “participatory” relationship. Children have been denied a sense of their participation with trees. When it has been properly cultivated, perception of this participatory relationship can make the world positively pullulate with meaning. Such cultivation is by no means the only responsibility of the teacher – but it is a worthy one, and it is almost completely ignored. This short piece argues for its reconsideration.

*

Briefly, what do I mean by a perception of participation? Across a range of fields, in art and science, it has been shown that “the viewer partakes in the viewed.” This is expressed with different nuance and emphasis across a wide range of disciplines, but the similarity is more striking than the differences. Plato, “the virtuous man sees differently from wicked man.” Titus, “to the pure, all things are pure.” Coleridge, we “receive but what we give”. Proust, “the real voyage of discovery consists not of seeking new lands but seeing with new eyes.” Iain McGilchrist, “the type of attention we pay to a thing determines what we see.” Sam Harris, “how we pay attention to the present moment largely determines the character of our experience.” I have collected a whole file of others! Anyone who has seen Simons and Chabris’ gorilla experiment will have also been struck by its profound implications. We only seem to see what we’re expecting.

This is not to say that we each create our own world. The objective world – the table on which I write and the cup of coffee by my side – has a reality with a concreteness about which all would agree. But you do not have to be a Post-Truth relativist to say.. only up to a point. We may disagree with the exact percentages assigned by Wordsworth in Tintern Abbey (…of all the mighty world / Of eye, and ear,–both what they half create, / And what perceive…) but surely we can say that we bring something – and something important – to and into our perception. As Iain McGilchrist writes, “we neither discover an objective reality nor invent a subjective reality…there is a process of responsive evocation, the world ‘calling forth’ something in me that in turn ‘calls forth’ something in the world.”

*

If our perception can be participatory in theory, is there any sense in which this might be the case in practice. Let’s go back to our class of teenagers looking at the tree. To what degree might we say that they can participate with it?

- Their degree of sensory acuity. Married to an artist, I am aware that even sensory perception varies wildly. Shades of white and green that I can detect via a Dulux index card, she is able to pick out with enviable ease. Lucky children will have had their native sensory talents trained, so whereas one child might see the trunk as brown, another might actually see it as “burnt umber”. This is a richer – a better! – perception. In ways I suggest below, we can train this habit of seeing and attending to the world, and we should.

- Their ability to name. Talk of burnt umber brings me to the important power of naming in perception. It is one of the charming mysteries of perception that once we learn the name of something, we see or hear it pop up all over the place. This was Robert Macfarlane’s fear when the Oxford Junior Dictionary was recently updated with the words acorn, adder, ash, beech, bluebell and buttercup replaced by attachment, blockgraph, bullet point and committee. If we cannot name something, often we cannot see it. Those children who had learned the name of ash or cedar would have seen this tree differently, better.

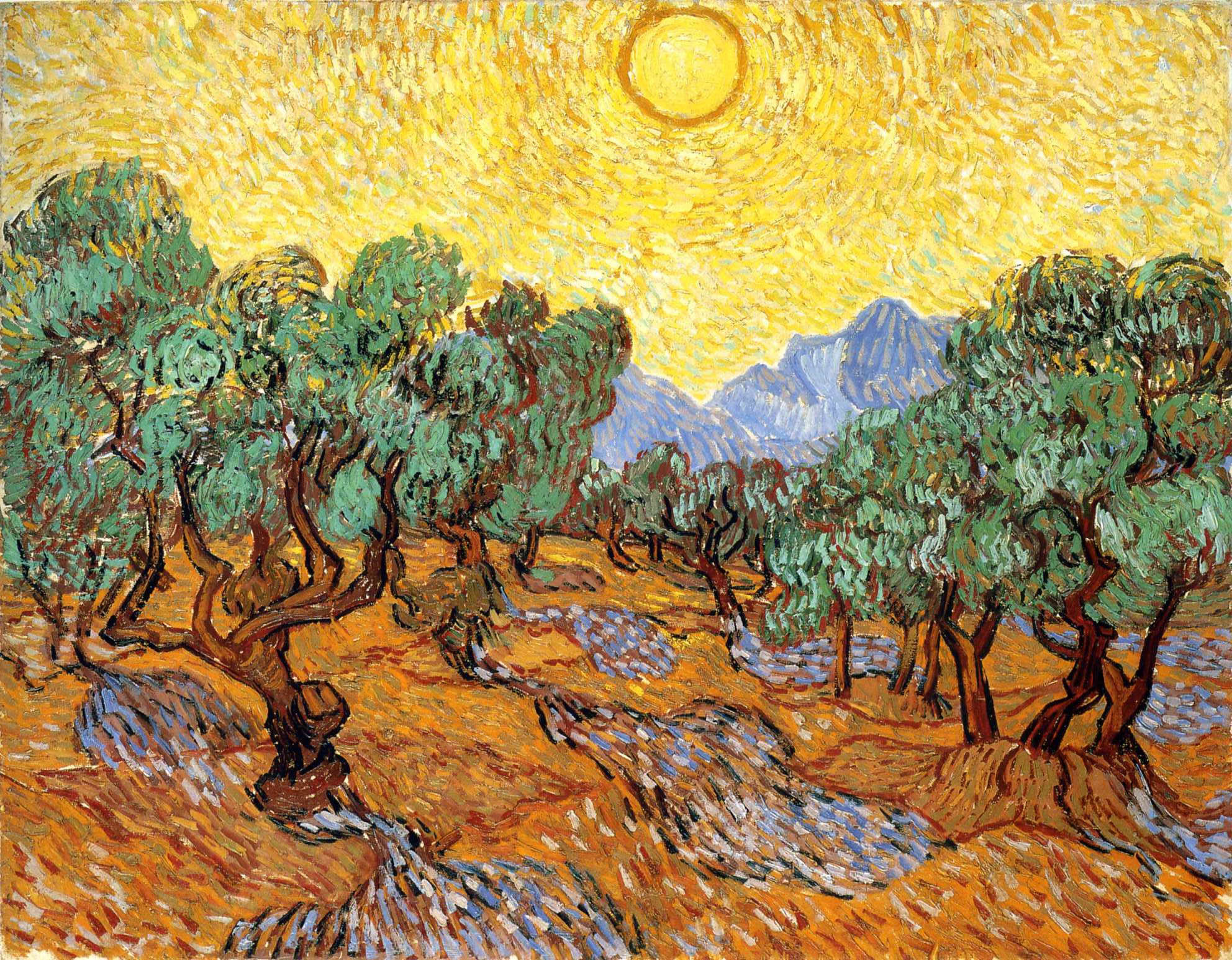

- Their imagination. But the part of perception that is most supplied by the viewer is that which can’t be supplied through the senses. It is that which is supplied by the imagination. It is the imagination that beams out of our eyes – Blake said we see “through, not with” the eye; Philip Pullman that imagination is a “way of seeing” – and it distorts the viewed to its own design. The way some people talk about the imagination, you would think it was another mere instrument for material success in the creative industries. But if it is well trained, it can enchant, animate and vitalise the world. The tree can once again dance before our eyes like it has to countless fortunate souls through the ages.

It is to that training we turn now.

*

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity… and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.”

William Blake

It is said that when Whistler was learning to paint in a new style, a woman complained when looking at one of his canvasses. “Well I never saw a sunset that looked like that,” she said. To which Whistler replied, “But Madam, don’t you wish you could?”

Either we have to write off the perception of artists and naturalists through the ages as delusional or a rare fluke, or we must conclude that they had access to something that most of us miss out on because of distraction or lack of proper training. We should want children to experience the world in this more vivid way. More and more children experience the opposite – a growing alienation from the world, a growing cerebralisation whereby they become trapped in the prison of their own self-consciousness, unable to fully participate with the world. The “Shades of the prison-house begin to close /Upon the growing Boy.”

In one sense, our job is a negative one. We should be alert to what form these “shades” might take and try to prevent their encroachment. I have a particular fear of the word “only” for growing children myself, as in “You fool! That grove of trees by the edge of the park that you thought was a magical wood is only a thin line built to mark the border with the supermarket.” etc. Picasso, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist after growing up.” Rousseau, “Nature wants children to be children before being men. If we want to pervert this order, we shall produce pernicious fruits which will be immature and insipid and will not be long in rotting….Childhood has its ways of seeing, thinking, and feeling which are proper to it.”

However, there are more positive jobs to do too. As teachers, we can influence what a child “brings” to his perception, even beyond the capabilities with which he has naturally been endowed. How might we do this?

Here I intend merely to point to a few directions of travel, along the paths suggested above.

Sensory Acuity – Attention Exercises

We said above that a child’s powers of attention can be trained. In a world of attention deficit, it is even more important. How can teachers and parents do this?

- Sensory Deprivation. One of the best ways to enhance one sense is to block out others. Blindfolds (e.g can you pick out a tree in a wood that you have only encountered when blindfolded?) and ear-plugs (e.g. lying in a field and writing down what one sees and feels) are invaluable aids to reflection. The best series of exercises are those suggested by Joseph Cornell in his Sharing Nature books, and children should be invited to enjoy such exercises regularly.

- Close Inspection. As we grow older, we seem to be further and further removed from the practice of investigating the world at first hand. This should not be so. Games such as Shrunk (using a magnifying glass in nature and describing what one sees) or dropping a wooden square and limiting one’s descriptions to its contents help delimit the scope of children’s attention. We should help children develop the habit of becoming rapt, a word that still carries with it its amplified meaning of rapture.

- Hunting. Bug Hunts; Tree and Flower Hunts; Cloud Hunts; Colour Hunts. Perhaps more sensuously designed field guides for children and teenagers could give more verve to the sport, and smart phones – properly used – could be of great service, especially if they add a competitive element. A leaf identification app has greatly helped me see more and see better.

- Breathing. Mindfulness has become common practice in UK schools, and rightly so. The ability to use breath to still the mind should be second nature to teenagers, and is a special aid in the appreciation of nature.

- Drawing / Craft. Most children, except those singled out as gifted, work less and less frequently with their hands as they grow older. The effects of these pursuits are too often only considered with respect to the quality of their output, rather than their impact on children’s attention. Sketching an animal’s footprint, taking a rubbing from the bark of a tree, making a bird’s nest / a crown / a mask / a dream-catcher / a Green Man can all help children see the world. Ruskin, “if you can paint one leaf, you can paint the world.”

- Context engineering. The Romantics wanted their poetry to “defamiliarise” their readers, their diction and imagery chosen to pierce the “film of familiarity.” Canny teachers can engineer context (e.g. what constitutes a classroom; who constitutes a teacher) to achieve the same effect and help their students see the world anew.

Of course, it may be that such activities are even richer when combined. Children could for example be played Debussy’s water music – training their ears – and be asked to respond using a ranging of materials from acrylic to sand. As long as training attention is held as a priority, anything can be attempted.

Naming – Knowledge Exercises

“We could never have loved the earth so well if we had had no childhood in it… These familiar flowers, these well remembered bird notes, this sky, with its fitful brightness,these furrowed and grassy fields… such things as these are the mother tongue of our imagination.”

George Eliot

Children used to learn the names of things more than they do today. In the 1950s, many schools had a regular Nature Study period in which children would learn the names of different trees, birds, flowers and their parts. It is my belief that these children therefore saw more than they do today.

It was easy to characterise such lessons as mindless or rote, but it was a mistake to do so. The champagne was thrown out with the cork. It is possible for teachers to pass on such names with zest. The evolving practice of mnemonics, buffeted by the proliferation of Mind Maps and fun technology like LeafSnap and Memrise, has made this even easier.

What is required, then, is a vibrant new series of books, field guides, “knowledge organisers” and the like that can introduce vocabulary and knowledge of the natural world to a new generation. Until that point, there are plenty of old books that will do the job – and parents/teachers can of course make their own. Nouns are one thing, but it is also possible to memorise a rich and expanding store of verbs, thereby animating the world with motion. How much easier to see a tree’s leaves in detail when one sees it leaves not just waving, but trembling, quivering, rippling.

Rather than being mistaken as mindless and mechanical, Memory is rebooted in this way to its older form, a dynamic way of interacting with and of seeing the world.

Imagination – Imaginative Exercises

With memory once again enthroned as an engine of perception, children should then be encouraged to use the contents of their memory in imaginative, “forgetive” (in Owen Barfield’s phrase) ways. Here are a few ideas, very few of them my own:

- Imaginative writing, including poetry writing. When taught for the purpose of passing exams, creative writing can be reduced to something of a box-ticking exercise: “include one simile, one metaphor etc.” When seen as an agent of perception, it can help forge new connectedness in the minds of children. The anthropomorphisation of otherwise inanimate objects is especially effective in this regard, giving agency and consciousness to things that usually characterised as inert and mechanical. As recommended by the Poetry Foundation, “one of the pleasures of writing poems is that you can tell lies without getting into trouble! It’s just using your imagination…Encourage children to be wild and imaginative with their lies avoiding the obvious or the dull (the moon is made of cheese). Give them a few examples of what they could write: e.g. The sea is made of blue ink and green paint; The sea hates it when it’s drawn as a wavy line.” Generally, despite what I wrote earlier about exam-preparation, structure should not be seen as the enemy of the imagination. Thought-provoking structured exercises such as Describe This Painting or Describe a Photograph ( • Who is the subject of the photograph/poem? What makes you think of them? Where they are most likely to be, what they would be doing, what they would be wearing? What objects might they be holding or have near them? • Decide the moment that the shutter clicks. Catch your subject in movement or stillness. Imagine how they would look, what gesture or expression the photograph has caught.) can produce unprecedented imaginative responses for children who have not had prior practice.

- Anthropomorphic Games. For children put off by creative writing, anthropomorphic exercises can be done orally too. Tree Stories, for example – children decide what type of person a tree / flower / etc would be if they could talk. Or Role-playing: children imaginatively inhabit a dandelion or a woodpecker and imagine life from their perspective. So much children’s literature can aid teachers in this respect, and the characters of these inanimate objects can be drawn out, discussed and legitimised.

- Inventing names for colours. This is a great metaphor-making game, which helps children to pay attention but also to vivify the world for them. Children should be encouraged to think about shades, tones, subtle differences and where the colour is found. They should be encouraged to be as inventive as possible, e.g sunken treasure cove aquamarine. Children can use colour charts for specialist paint companies (all available online) as inspiration.

- More metaphor-making games. These were also suggested by the excellent Poetry Foundation. “Anthony Wilson will often begin by holding up a triangle of plain paper and asking pupils what it is – it’s a hat, a headscarf, a sail, a mountain, a sandwich, a bikini bottom… The pupils immediately get the idea and love using their imaginations to transform the one-dimensional shape into a range of alternative objects of differing scale.” Lawrence Bradby “uses a large ball of paper –a cauliflower, a planet slowly turning on its axis, a tear rolling down a face –and then develops this to make a list poem, using many children’s ideas and shaping the poem together.”

*

“To speak truly, few adult persons can see nature. Most persons do not see the sun. At least they have a very superficial seeing. The sun illuminates only the eye of the man, but shines into the eye and the heart of the child. The lover of nature is he whose inward and outward senses are still truly adjusted to each other; who has retained the spirit of infancy even into the era of manhood. His intercourse with heaven and earth, becomes part of his daily food. In the presence of nature, a wild delight runs through the man, in spite of real sorrows. Nature says, — he is my creature, and maugre all his impertinent griefs, he shall be glad with me…Crossing a bare common, in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration….Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. ”

Emerson, Essay on Nature

We are frequently told that we live in an empirical and reductive age, in which nothing is of value unless it can be measured. I nevertheless find it interesting and encouraging that many of the innovations that have taken hold in education in recent years have been as interested in the interior as the exterior, e.g. growth mindset, mindfulness and wellbeing.

Utilitarian materialism supplies a meagre dollop of meaning to the viewed – merely the utile. But when we sit beneath a tree and feel a subliminal aesthetic calm in a way we (certainly I!) cannot put into the words, we feel the distant echo of a relationship that has too often been undernourished. If we are ever going to encourage children to see the world more richly, it will come through the enhancement of the above faculties. It might not need to happen in the classroom; it could happen in lunchtime clubs, on the weekends and in the holidays. Some such as First Hand Experiences and our Imaginarium are trying. I hope this piece has made the case for why doing so is both important and possible. Join us!